Jarno Puff

All the right signals

The CTO of OEM comms and other systems provider LikeAbird gives Peter Donaldson his take on how to meet customers’ requirements

An early enthusiasm for computers and aviation, combined with talents that leaned more towards the practical than the academic, led Jarno Puff, now CTO of uncrewed subsystems developer LikeAbird, into an eclectic career that has encompassed industrial robotics, computing, UAV design and HMI development, emergency aviation and cloud computing. These coalesced into the development of comms for professional-grade UAV systems, including those used in BVLOS missions managed using the cloud.

He first encountered remotely controlled aircraft as a hobby in the early 2000s through a friend who worked in a model aircraft shop. He recalls having difficulty with the left-right control reversal that takes place when the aircraft comes back towards the operator, and it occurred to him that something like an aircraft cockpit and a set of virtual reality goggles would make them much easier to fly.

Virtual cockpit experiment

The chance to develop such a system came in 2003 through his involvement with Italian volunteer civil defence emergency aviation. UAVs were still a hobby at that point, as by then he had built a career in industrial robotics, automation and computer networking.

Invited to give a talk about UAVs at the ITT Galileo Ferraris college in Verona, there he met Prof Athos Arzenton, who was involved in Verona’s voluntary civil defence association, which he invited Puff to join. On the first civil defence exercise he attended he met fellow volunteer Davide Burei, a light aeroplane pilot and instructor. Together with another friend they founded the voluntary association’s Emergency Flight Department (EFD) to experiment with the use of microlights and UAVs.

“There were no flight controllers available like there are today, so manually controlling a drone was a cost-effective way to get situational awareness from the air. You just needed a licenced ‘real aircraft’ pilot to fly the drone,” he says.

“We demonstrated this in 2006 using a test pilot with no RC model experience. He carried out aerobatic manoeuvres we couldn’t do as experienced RC pilots, which was impressive and confirmed our supposition.”

The system that enabled this was developed in collaboration with a group of German companies, one of which was involved in developing the simulator for the Eurofighter Typhoon. “We used the original Eurofighter simulator throttle, stick and pedals with a CANaerospace-to-PPM converter and a Futaba RC handset,” he says. “The FPV display was based on Olympus video goggles and a 2.4 GHz analogue link with six patch antennas and a diversity receiver.

“A Sony Video Walkman GVD1000E was used to record live video on a MiniDV cassette. An analogue video overlay generator was used to overlay basic telemetry data on the live video.”

During this period, he recalls, UAVs were established only in the military, with no rules for civil use. “From a technical point of view, the main challenge was in developing the video and C2 links using legal frequencies and power levels,” he says.

Puff spent about 10 years working with the EFD while running his first start-up, a storage area networking (SAN) consultancy as his main business. SAN is a key technology that, for example, enables multiple servers in multiple data centres to share storage facilities, adding redundancy and reliability. The UAV HMI work led him to found Advanced Aviation Technology (A2Tech) in 2005 to develop the systems into industrial-grade equipment.

In this time frame, however, cost-effective autopilots, miniature stabilised camera gimbals and low-cost, user-friendly multi-copter UAVs became available. These developments reduced the pilot workload involved in UAV operations, including real-time FPV piloting.

By the time he left Italy, in 2014, for Germany to seek further finance to develop A2Tech, the EFD was using small, multi-copter UAVs such as the DJI Phantom series for local situational awareness, as well as manned light aircraft for long-range missions.

Cloud formation

He traces his involvement in robust networking and data centres back to when he was working for an Apple computer reseller in the mid-to-late 1990s. “We had a customer, a music production company, that needed to transfer large amounts of data from one computer to the other, and to share the data at high speed,” he recalls. “That got me into Fibre Channel, a technology that enabled 1 Gbit/s networks when Ethernet was at 100 Mbit/s.

“Now everything is connected. BVLOS fleets are purely cloud-based operations using either cellular networks or satellite constellations,” he says. “Data centres are the heart of long-range operations, particularly custom BVLOS applications running VPNs, fleet management, data post-processing, and for the cellular data links in which end-to-end comms are based on global IPX backbones to transport data.”

The value of data centres to airborne surveillance was demonstrated during his time with the EFD in combination with Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) 3G cellular technology.

“Back in 2010, when we used light aircraft, we used data centres to send snapshots via UMTS to an image server so that the emergency operation centre could retrieve them instantly,” he says. “That would not have been possible without the use of a data centre.

“Since then, the combination of cellular comms and data centres has had a profound effect on drone operations, with multinationals such as Amazon running fleets of them from operations centres using 4G or 5G links for drone-to-cloud comms,” he notes. “Only the availability of these mobile networks enables BVLOS drone fleets operations; RF links or satellite links are not an option.

“There are a lot of developments in this field, and the large mobile network operators see new business opportunities in drone-specific data plans and services with a guaranteed quality of service.”

Creating and setting up VPN-protected drone-to-cloud comms systems correctly is a complex task, he says. “You need to deal with topics such as redundancy, latency, bandwidth, signal coverage and integrity, back-up links such as satellite, local regulations, rules and approvals, and scalability.”

Integrated comms

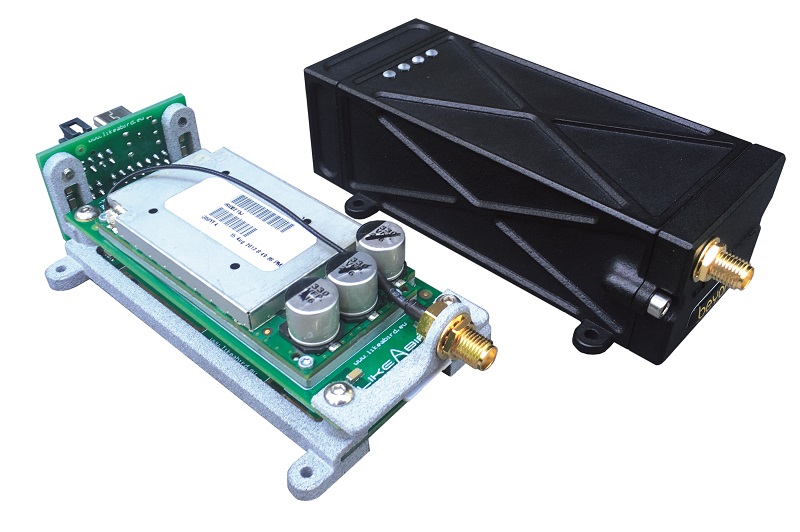

In 2019, Puff founded LikeAbird, effectively as a successor to A2Tech, to focus on OEM electronics and engineering services for uncrewed systems. “My primary job is watching the market, its evolution, needs, wants and available technologies,” he explains.

“My background knowledge ranges from companies and materials to components and software applications, so I look for parts that are best suited to each specific solution.”

Current projects include developing a backpack GCS and router for rapid deployment (see our DroneX report in UST 46, October/November 2022), and a new generation of airborne smart router with link fusion between RF bearers, redundant 4G/5G cellular comms and satellite links.

The challenges faced when integrating cellular and satellite comms into UAVs often depend on the requirements and expectations, he says. Size and weight remain a perennial challenge in airborne systems, while fusion of cellular and satcom links for smooth end-to-end comms are essential to meeting evolving market expectations. “Prices are also a challenge, as our solutions are not as cheap as those that customers sometimes put together in-house, or those that come from China.”

UAV developers often want to create their own comms solutions but can run into difficulties, perhaps stemming from a degree of overconfidence. “The average age of drone company founders and owners is below 30, and most of them have technical affinities stemming from a Linux and/or embedded systems background,” he says. “That leads them to think they can and should come up with all the solutions in-house, as it seems to be more cost-effective.

“That might be right for some proof-of-concept builds, but in production at scale it could result in systems that do not perform as well as expected, and lost market opportunities. The issue is that they don’t stay focused on their core business, whether it be manufacturing or operating drones.”

Resistance to the cost of its industrial-grade cellular comms systems from UAV developers is why Puff decided to develop satcom systems at LikeAbird, as these essential back-ups also seem to serve as a back door into the market. “If we sell them the satellite systems, they then tend to ask, ‘Can we combine satellite with cellular for smooth switching?’ Our answer is yes, but you need our router. That usually gets them interested.”

At LikeAbird, he focuses on building modular, scalable solutions that are as near to the plug-and-play ideal as possible, which presents challenges from both the hardware and software perspectives, he explains.

“Due to their modularity, our solutions are often larger than others. Developing hardware is expensive, and the variety of unmanned systems operations is very wide, so I prefer to develop modular hardware blocks that can be easily adapted to different operational scenarios instead of specific printed circuit boards for each one.

“On the software side, coming from the data centre world, I’m used to thinking in a scalable manner and about how the software solutions should be open, modular and flexible.”

The extent to which the solutions that are delivered are truly plug-and-play really depends on the final requirements, expectations and use cases, he notes. “Sometimes the whole system is truly plug-and-play, but sometimes it applies to the hardware only, as some customer interaction with Linux scripts or interpretation of protocols is required.”

Looking to the future, he expects UAVs and other uncrewed systems to play an increasingly important role in society, with urban air mobility (UAM) ramping up quickly to offer a new means of personal transport.

That raises the issue of safety. “The reliability that we are used to seeing in crewed aircraft must be engineered into drones and UAMs,” he says. “I’m not willing to risk being hit by a falling drone just because it has lost a propulsion system.

“That is a cost factor, but there should not be a loophole for drones and UAMs that permits less reliability and safety for the sake of faster adoption and shorter time to market.”

More specifically, he also anticipates major improvements in satcom installations. “They will be more miniaturised, more cost-effective and have better airtime plans. Satcom is mandatory for flight termination and/or as a back-up link in case 4G/5G coverage is not available.”

As to personal ambitions, he would be glad to accept a job offer from Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works. “Joking aside, I will be increasingly focused on comms projects across the globe and creating the first cross-continent low-latency drone network,” he says. “But I don’t think I will see the fulfilment of that dream in my career.”

Jarno Puff

Born in 1973 in South Tyrol, Italy, and educated in the region, Jarno Puff excelled in electronics and mechanical subjects at school. He was captivated by the early games consoles and PCs that were his introduction to electronics, IT and computer programming. He also developed an enthusiasm for everything that flies, his dream job as a youngster being to fly either jet fighters or helicopters.

He pursued further education at the Fachhochschule fur Elektronik und Elektrotechnik) in Bozen (Bolzano). Then came a specialist course in industrial robotics in the same city, followed by a year’s national service in the Italian Army.

Technical, engineering and training jobs with an Apple reseller, surgical laser manufacturer Stem Laser, and major storage area networking provider McData followed.

In 2003, he founded his first company, SAN Experts Facility, which until 2016 provided consultancy and other services to the storage area networking market.

Also in 2003, he co-founded the Emergency Flight Department (EFD) of the Italian Volunteer Civil Defence Association, a pioneer in the use of UAVs and other low-cost aerial platforms in the voluntary sector. He worked there for 10 years.

His involvement with the EFD led him to start Advanced Aviation Technology (A2Tech) to develop industrial-grade UAV systems and cockpit-style GCSs, running it alongside SAN Experts Facility from 2005 to 2016.

Since 2018, he has served as the CTO and instructor and speaker at 3D Xperts, which provides education and training consultancy in additive manufacturing.

These days he is also CTO of LikeAbird, which he founded in 2019 as a successor to A2Tech, focusing on OEM electronics and engineering services for uncrewed systems.

UPCOMING EVENTS