Pam Oakes

An automotive maintenance expert and ADAS educator tells Peter Donaldson how she started out fixing her colleagues’ cars on the side before switching to the job she loves

A key consideration for the long-term acceptability of fully autonomous vehicles on the open road (SAE Level 5) is the quality of support – including updates, maintenance and repair – that the automotive industry can provide for vehicles expected to last two to three decades and pass through the hands of multiple owners.

To gain an insight into the challenges that such support involves we spoke with Pamela ‘Pam’ Oakes, who has years of experience running automotive repair shops and training technicians to work on increasingly sophisticated technologies, including advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS).

Fourth-generation tech

Oakes describes herself as a fourth-generation automotive technician, tracing her connection with the discipline to a great-grandfather who changed career from beat officer in the Detroit Police Department during World War I.

The move came at the urging of his wife, who had just had a baby (Pam’s grandfather) and wanted her husband to be in a less dangerous job, anticipating the prohibition of alcoholic drinks in the US and the crimewave that would accompany it.

Success as a truck mechanic and production manager followed, leading him to open his own workshop, where, ironically, he ended up fixing trucks used by a group of notorious bootleggers – the Purple Gang. “I remember asking him what they did while he fixed their vehicles: drank and played cards,” Oakes recalls.

Her grandfather and father, Jerry, went into the same industry. By the late 1960s, Jerry had become a steering and suspension specialist, who set up the Daytona-winning Chevrolet Corvettes and Corvairs in the 1967-68 seasons.

A child of the 1960s, Oakes grew up in Detroit around muscle cars and the people who built, fixed, tuned and raced them. Today, following a varied career with major automotive service companies in the US, she runs autoINENG.io, her own ADAS consulting business.

Data for Level 5

Decision-making software in autonomous vehicles relies on information from ADAS sensors. Reliable data on their performance under diverse road, traffic and weather conditions is essential to build the trust that enables authorities to certify vehicles to use Level 5 autonomy.

“There are quadrillions and quadrillions of bytes of machine-learning data that need to be gathered before we can even think about Level 5,” Oakes says.

Ensuring the data from these sensors remains reliable throughout the service life of the vehicle fleet, even after accident repairs and demanding recalibrations, is a major challenge for the industry, placing vehicle technicians in maintenance and repair shops in the frontline. They are also in the frontline of consumer education.

“The consumer needs to know what is on their vehicle, why it’s there, and how the interaction with ADAS technology affects their driving. Even more than a ‘check engine’ light, it is important to have an ADAS warning checked out immediately because it is all about safety,” Oakes says.

Some devices, such as proximity sensors mounted in bumpers and cameras in door mirrors, are easy to damage in even minor knocks and scrapes, while others that feed sensor-fusion software, such as bioptic and stereoscopic cameras, radar, Lidar and night-vision cameras, are more robust but not invulnerable.

Therefore, vehicle technicians need to understand their operating principles and recalibration requirements. Even routine maintenance procedures on ADAS-equipped vehicles demand a higher degree of specific knowledge.

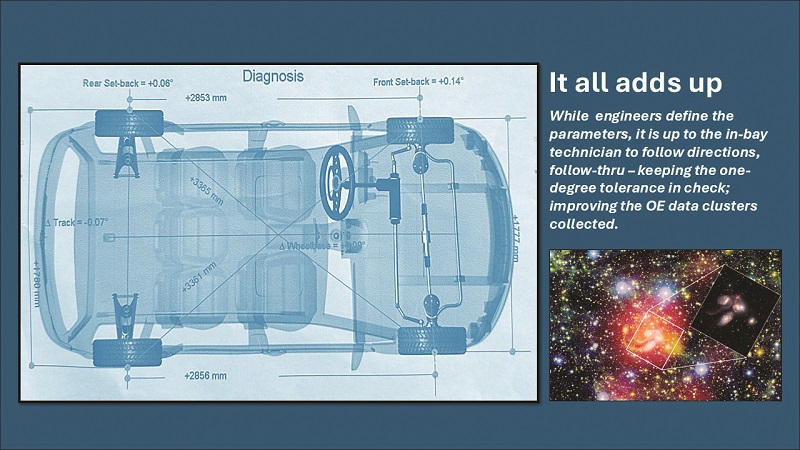

“A simple, four-wheel alignment may now require the vehicle’s steering angle sensor (SAS) to be reset. If the technician does not research the vehicle’s equipment before service – and the manufacturer requires an additional ADAS recalibration like that – it may go unchecked.”

Recalibration issues

Regardless of the technical education of the consumer and technician, the biggest challenge in the repair of ADAS-equipped vehicles is the size of the bill, as sensor replacement and recalibration are expensive, often to the point of being prohibitive to the average consumer.

“I recently saw a vehicle – fresh from the body shop – with an obvious camera issue: one outside mirror had a camera, the other did not,” Oakes says.

“When I asked, the repair manager told me that the owner had replaced his own mirror before the accident as the cost for a camera-equipped unit was approximately $750, with installation and ADAS recalibration costing extra.”

While recalibration requirements and complexity vary between sensors, vehicles and installations, these differences count far less than the technician’s skills, and their development and upkeep through education and training. Oakes argues that the installation and resetting of a vehicle’s sensor technology is similar to any other muscle-memory task, unlike diagnosis and programming.

These systems are highly software-intensive, so dealing with bugs and keeping them up to date is a constant state of focus for Tier 1 suppliers and automotive manufacturers working together to gather as much operational data as possible.

However, some adjustments need to be made to improve data quality and tighten clustering – the process of grouping similar sets of data points to make it easier for machine-learning algorithms to interpret and act on the information.

“Sometimes, an OTA [over-the-air] update will suffice; most times a technical service bulletin is issued with new procedures. Unfortunately, these adjustments are usually made when a vehicle requires calibration/recalibration – usually post-accident.”

As with the components of any networked vehicle architecture, ADAS sensors and control modules have self-test capabilities, and they can also provide diagnostic information to technicians on demand through databuses such as CAN and, increasingly, Ethernet. However, this is not a substitute for the fundamentals.

Oakes emphasises it is important to check the primary and secondary electrical integrity. The first ensures sufficient, stable power is getting where it needs to go, while the second focuses on communication and signal quality between sensors and modules, etc.

“Then, it’s time for the pre-scan check of the vehicle’s electronic ‘health’. This testing allows a technician to see which components are operational and which have issues.”

Start simple

Oakes emphasises that shops aiming to work on ADAS and, eventually, autonomous vehicle systems don’t necessarily need to make a big upfront investment in specialised equipment. Instead, the priority should be to evaluate the suitability of the workspace and research the shop’s vehicle-specific needs.

Environmental factors in the workshop are critical for successful ADAS calibration and recalibration. These include a near-perfectly level floor, controlled overhead lighting and minimal external visual interference, such as from windows, for example. These elements are essential to ensure accurate sensor and system alignment.

Oakes advises shops to tailor their equipment choices to the types of vehicles they most commonly service and the ADAS functionality built into them. So, they might start with a basic calibration tool, such as a trihedral target, which is a relatively low-cost entry point, and expand to more comprehensive systems if necessary.

While system complexity increases with the level of autonomy, the same is not always true of the demands imposed by calibration. With Tesla, for example, as the technology reaches Level 3 and beyond, costs will increase, although the difficulty involved in returning the system to the original calibrated settings will not necessarily increase in proportion.

Oakes believes that in future, most recalibration will come to rely on the Internet of Things (IoT) and OTA capabilities. “For now, technicians need to treat each vehicle as a unique entity, even if they just calibrated/recalibrated a duplicate model days before.”

Learning process

Certifying cars and trucks for Level 5 autonomy, and ensuring they remain safe to operate, depends heavily on obtaining high-quality data – and that rests upon the shoulders of the technicians performing ADAS recalibrations, who need to follow procedures exactly and double-check their work.

“Unfortunately, lack of knowledge, management push to get the vehicle back on the road and the assumption that all vehicles are alike hamper the learning process today, so too few recalibrations hit the manufacturer’s ideal mark,” Oakes cautions. “The information provided by poorly calibrated car or light trucks will take time to get banished into the dead data universe.”

Ensuring there are enough technicians with the skills required to keep the autonomous vehicle fleet roadworthy will require the industry to pay them for their knowledge and provide good working conditions.

“Don’t abuse them by keeping them in the bay past 40 hours each week. After all, they are working on vehicles with more modules than the Space Shuttle!” she says.

Technicians also need adequate information about the systems they are asked to work on from vehicle OEMs and subsystem suppliers. However, it is not design engineers who typically write ADAS calibration/recalibration directions, but aftermarket technical writing companies hired by the manufacturers, and sometimes this can result in misinterpreted instructions.

“Between the manufacturer’s directions and classroom/hands-on training, the well-educated technician can recognise issues such as misnomers and – by consistent learning – will be able to correct them,” Oakes says.

Human communications

Oakes believes communication between the two worlds of sensor-system technology development and vehicle maintenance could be improved.

“They really need to get together because the engineers can explain to the technicians, ‘hey, this is why we are requiring these numbers, and why you don’t just move that stand back and forth for convenience just so you get a passing grade on your scanner’. On the other side, the technicians need to know how the system works and what to expect from the sensors. Having that interaction would really benefit everybody.”

Further, maintenance workshops and the technicians working on ADAS-equipped and autonomous vehicles face huge legal liabilities.

“When it comes to ADAS calibration/recalibration and driver safety, there is no cutting corners. That means, for example, that when a vehicle’s tyres require 4/32 in all around, the tread depth must either match or have more meat on the tread, verified beforehand by the technician photographing the tyres,” Oakes says.

“I have seen several examples within the past couple of months where an insurance adjuster was trying to convince the technician to perform a calibration/recalibration on a vehicle that had tread separation on two tyres. Not following the manufacturer’s directions exactly may lead to a court subpoena when a sensor fails to operate properly, and an accident leads to injury or death.”

Liability issues relating to autonomous vehicles will only become more critical as autonomy levels get higher and dependence on the technology increases. “It’s going to be interesting how it all plays out, especially in the courts.”

Pam Oakes

Pam Oakes grew up in the East side of Detroit and then Florida, passing through the public school system, where she excelled in mathematics and science. A misdiagnosed illness in her late teens forced her to turn down a fully-funded degree scholarship to Florida State University, but she used other scholarships to earn degrees in English, electronic engineering technology and computer programming.

A lifelong learner, she has numerous technical certificates and is now studying for a cyber-security degree.

While still at school, she took a job on a local newspaper, where she worked following her misdiagnosis, rising from reporter to editor, and fixing fellow journalists’ cars on the side. After 11 years, she found herself wondering why she wasn’t doing the thing she truly loved. “Six months later, I was turning wrenches, and 18 months after that, I started my own shop!”

Over the 20 years that she ran the shop, it grew from a one-woman outfit to a business employing 15 people, working on up to 9,600 vehicles per year.

Oakes took temporary retirement in 2015, before becoming a consulting automotive technology instructor in areas as varied as diesel mechanics, HVAC, AI/machine learning, ADAS and fleet management, working with both private companies and local government organisations. She has also applied for a patent for an ADAS device.

In late 2024, Oakes reopened her consulting business, autoINENG.io, which now provides expertise in ADAS sensor technology for workshops and technicians, along with expert witness testimony and help for clients in “navigating the complexity of automotive safety and technology” on a confidential basis.

She regards her father as her mentor. “Even though my great-grandfather gave me my first under-hood lesson when he showed me how to set the choke on our 1969 Plymouth, it’s my dad. I was fortunate to work with him a few years before his retirement. We still talk cars.”

Away from work, Oakes enjoys golf, and spending time with her partner (a fellow automotive industry professional) and their dogs – two rescued Great Danes.

UPCOMING EVENTS