Defence vehicles

(Image: Quantum Systems)

Unbent, unbowed, uncrewed

Rory Jackson investigates a range of the latest autonomous defence vehicles, and what they represent of the wars and security threats around the world today

Uncrewed systems exist to make people’s lives easier, taking on dull, dirty, or dangerous work from humans – and it is hard to picture more dangerous work than military duties.

So it is that over the last few years, the growing mélange of conflicts around the world has served a veritable overabundance of proving grounds for new autonomous solutions, while also exponentially increasing the demands being placed on their developers as they discover new tasks that drone and robotic systems could deliver for them.

Thus, the number of uncrewed systems in the world has proliferated, coming in forms hardy and long-lasting, but also as attritable or even autonomous self-detonating munitions. Technological adoptions are also moving quickly, with ISR sensors, heavy fuel engines and stealth-enhancing hull materials among the solutions rapidly sourced and delivered worldwide as uncrewed troopers multiply.

Swarm production

That multiplication itself is now a key factor between victory and defeat: as conflicts grow in number and scale, the simple ability to supply quality UAVs in massive numbers, and at short notice, will separate minor contractors from global defence leaders over time. Networked swarms of uncrewed assets, painting detailed strategic maps of warzones, and then executing all variety of tactical missions and operations, will determine the fate of nations as the 21st century draws on – but cannot become a reality without first establishing the manufacturing capacity for thousands of drones.

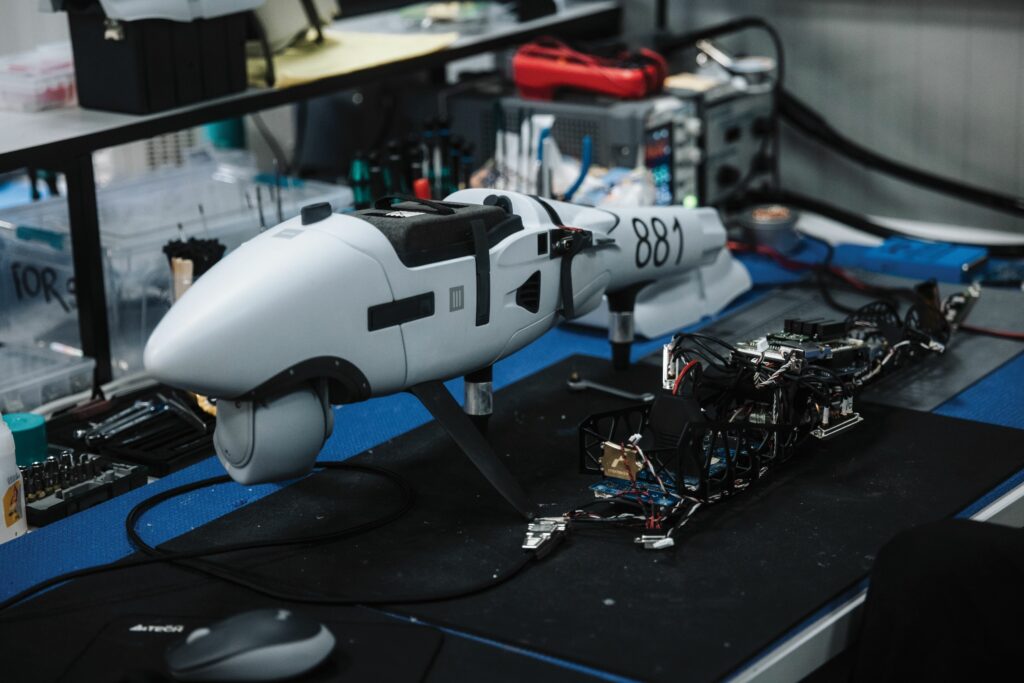

Amid its extensive contributions to Ukraine’s fight over the last few years, Quantum Systems has been laying such foundations because its customer demands now extend just past 2000 units per year (from just 200 UAVs only a few years ago), particularly of its ISR drone designs: the Vector AI, Reliant and Twister.

These are on-track to be achieved through highly automated new factory networks, resilient supply chains and prudent UAV design choices. All these are led and overseen by Alexandra Rietenbach, who is director of operations at Quantum Systems, and thus responsible for the German company’s production, supply chains, fulfilment, logistics and quality control.

“We have factories in the US, Australia, Germany, Ukraine, Romania and other countries too; but as we build new factories there and elsewhere, it’s important we keep the same production standards, flexibility and scalability in every entity at the same level,” she says.

“To scale-up production capacities and efficiency, it’ll take a mix of automation and skilled human workforces; but the difference between UAV manufacturing and, say, automotive production, is that UAV makers are readily expected to stay flexible and customisable.

“If you automate too much, you lock-in too much of your design, and you risk ending up like the German automotive industry: overproducing something that’s not meeting the demands of your customers.”

A critical first part of Quantum Systems’ factories is composite production, with its capabilities in this regard including wet lay-ups (beyond the industry standard use of prepregs) and automated production of subassemblies to ensure the right technology is used as needed for the airframes.

Following this, system integrations are typically carried out manually, not only enabling ad hoc modifications such as soldering-in new chips or mounting customer-preferred radios, but also the ability to scale production up or down by adding or reducing shifts around the clock as needed.

“At the moment, most of our factories just run one shift, and that’s a controllable factor we can adjust to double our production times within a month if needed,” Rietenbach says.

From her perspective, the biggest potential automation gains lie in end-of-line testing for completed UAVs. Each drone must be motor-tested, visually inspected, flown and more before shipping; several such checks, which used to take 30–60 minutes, are now done in 5–10 minutes through measures such as indoor flight-testing rigs or X-ray scanners for checking the integrities of circuit boards and subassemblies.

(Image: Subsea Craft)

After testing, considerable automation may also be brought to warehouse management (as seen in various UAV and UGV operations to that end), cutting lead times by eliminating manual scanning and stock-taking tasks.

Naturally, use of robotic arms and other automated machinery are also proving useful for streamlining assembly stages for the ISR UAVs, while retaining flexibility through such systems’ capacity to be reprogrammed.

“Design changes are key too, such as those visible with the new release of our Vector AI drone, which brought in new functionalities over the Vector but also better producibility, scalability, and ease of repair and maintenance,” Rietenbach notes. “Before, for instance, Vector had a complex interior rig system, but now users of Vector AI can directly access the main system boards just under a removable hull fairing.”

The company also anticipates additive manufacturing being increasingly important to outputting higher numbers of aircraft. Its in-house additive printers are utilised in rapid prototyping and ‘fail-fast’ maturation of new UAV designs, but it is also starting to explore printing larger sizes and quantities of parts, given the speed, consistency and weight-saving that military customers see in modern CAD-driven printing.

Rapid deployment

As conflicts and asymmetric warfare spring up around the world, uncrewed systems are valued not just for the efficiency with which their autonomous operations can execute missions, but also the rapidity with which new vehicles or robots can be produced in entirely new, requirement-specific form factors (particularly when the need to consider pilots or passengers is absent).

UK-based Subsea Craft demonstrated this decisively with its MARS USV, having unveiled the 4.5 m long vessel in May 2025 after designing, building and testing it within 100 days. The company attributes this speed to a combination of quick decision-making, myriad supply chains for ensuring on-demand availability of equipment, and its engineering teams’ robust skillsets across timely hull construction, system integration and control code writing.

“Since then, this USV has done extra trials in the US at the annual Trident Spectre event, as well as doing about four months of trials at the other end of the Pacific with the Australian Maritime College,” says Graham Hepworth, chief engineer at Subsea Craft.

The vessel displaces just over a tonne, and is powered by a Yanmar diesel engine driving a Hamilton water jet thruster system, enabling top speeds of 35 kts and ranges of roughly 300 nm, with a Starlink system providing its primary comms over any distance with coverage, although data link redundancy is additionally enabled through either radio for LOS distances or 4G wireless modems for cellular coverage.

“Exact ranges and endurances are, of course, payload-dependent; the craft’s been designed principally to take two Altius-600M launching munitions, but there’s natural capacity to integrate electronic warfare systems, ISR and more,” Hepworth continues.

“It has a dedicated payload space for integrating different devices very easily, while also coming as standard with a GPS-INS-DVL unit for GNSS-denied transits with decent accuracy.”

The USV is additionally tapped for applications including maritime domain awareness, persistent ISR, counter-UxS and full spectrum ISTAR operations. Some CONOPS also include launching groups of small UAVs for aerial ISR to further inform and support the USV and its operators.

The MARS is, surprisingly, Subsea Craft’s first USV product also. The system shares some minimal technology with a prior solution from the English company, the VICTA underwater vehicle for diver delivery applications (as of writing, an optionally crewed version is in development).

“MARS is mostly using its own specific equipment, but the two have common control systems and electrical architectures, particularly in terms of the modular approach we’ve taken with the electric power system, and sharing battery technology between the two that we’ve developed to deploy on both craft,” Hepworth adds.

“We have an in-house electric powertrain engineering stream that we’re working on, almost entirely independently of either craft, so that we can, in future, put any sort of vehicular ‘wrapping’ around it that we or customers wish for.”

Intercept and destroy

As the ongoing conflict in Ukraine has shown, UAVs are not just a tool for flying high-up surveillance or backline logistics far and safe from the actual warzone; in reality, some specific configurations are serving as critical frontline tools and actors for soldiers, both on and beyond the frontlines.

UK-based Skycutter is a company designing and manufacturing such cutting-edge UAVs for Ukraine, using rapid, weeks-long feedback cycles to refine how uncrewed systems can better serve war fighters in fast-evolving conflicts.

One example is the company’s SC-ISR, designed as a backpack-deployable drone stowed complete with its controller, ground radio and antenna mast, along with a 25 m cable.

“That means that the operator can be recessed and hidden away relative to the comms equipment while monitoring or piloting the SC-ISR,” explains Vincent Gardner, operations director at Skycutter.

(Image: Skycutter)

“It folds out of the bag and can be flight-ready in 90 seconds, and we’ve chosen to integrate a very high-end ISR payload as standard, which features a 40X optical zoom EO camera and a 6X optical zoom thermal camera in a 3-axis gimbal. With that thermal camera, it can confirm sight of people at about 1–2 km away, and the EO camera can recognise vehicles from 5 km or people from 3 km.”

As well as being built for EW-resistance, the SC-ISR comes with an obstacle and interceptor avoidance capability. Through an onboard sensor array, it achieves 360° situational awareness. If signatures consistent with interceptor drones are detected inside a radius bubble, the flight controller instigates evasive manoeuvres away from the signals at or near its top speed of 27 m/s (100 kph), while alerting the operator accordingly (who may otherwise be concentrating on a mission target rather than the UAV asset or approaching hostiles).

Skycutter maintains a policy of integrating the latest-generation energy systems from any trustworthy source, extensively validating sample battery cell batches in-house, to check them against their datasheets and understand their safety qualities before using them on UAS products. The SC-ISR henceforth comes with a 666 Wh battery, enabling flight times of 75 minutes for the backpackable quadrotor.

The company additionally produces the SC-Orca, a one-way effector capable of 50 km flight ranges through a 54 Ah battery pack. It carries up to 10 kg of payload, and while it is often remotely piloted for much of its lifespan, it integrates an autonomous last-mile guidance system in order to intelligently home-in on an operator-selected target without reliance on a data link.

“SC-Orca comes with FPV goggles, but after it descends below 100–200 m altitudes, the end-user is likely to lose the signal from it, so that autonomy is key for how it continues on – including exceeding 100 mph [161 kph] top airspeeds – and hits its target,” Gardner says.

An alternate version of the SC-Orca is produced commercially, named the SC1200, which maintains the SC-Orca’s key features but adds reusability, folding arms and custom payload integration capabilities. The system is particularly aimed at operators that need to deploy in contested airspace environments for extended periods, such as for counter-UAS detection payloads.

For even longer endurances, heavier payloads and motor redundancy, Skycutter also has its Gryphon UAS in serial production, which is a hexacopter deployed globally by customers for defence and commercial applications, capable of flying a 5 kg payload for just over one hour on its standard batteries, or for two hours with an Intelligent Energy fuel cell. Other powertrain configurations are also available upon request, such as a higher-than-standard energy pack enabling a 16 kg payload to be carried for 20 mins (though this format raises the Gryphon’s MTOW from 25 to 30 kg).

Persistence surveillance

Platform Aerospace, a company headquartered in Hollywood, Maryland and recently expanded to the UK, is best known for its Vanilla ultra-long endurance Group 3 UAS. The 36 ft (11 m) wingspan aircraft is being trialled and operated in a number of high-profile defence projects owing to its disruptive flight time capacity and up to seven payload installation points across its wings and body.

As Jim Snow, chief growth officer at Platform Aerospace tells us, “Vanilla is an ultra-long endurance Group 3 UAS [55–1320 lb, or 25–598 kg], which holds the world record for continuous, un-refuelled endurance at 8 days and 50 minutes.”

Vanilla’s endurance, operationally useful payload capacity, and attritable cost profile suit the aircraft towards ‘Land Tactical Deep Find’ and similar multi-mission operational requirements.

“With an open, modular architecture, Vanilla can carry up to 68 kg of payload, encompassing anything from air-launched effectors, all the way to the other end of the spectrum with ISR, SIGINT, environmental and communications relay systems,” Snow continues. “With its endurance, Vanilla can travel great distances and loiter on target for days at a time while executing multi-mission operations – carrying multiple different SWaP-compatible payloads.”

Vanilla has also integrated non-kinetic air-launched effectors, anti-submarine warfare, environmental, meteorological and other payloads as part of a Phase 3 small business innovation research (SBIR) contract sponsored by the US Office of Naval Research.

Vanilla is currently aligned with the US Army as its service sponsor. It recently provided support during two exercise events for the Office of the Undersecretary of War and for other military partners. At the Arctic Edge exercise, Vanilla was operated from the Kenai Airport in Western Alaska: that exercise saw the Vanilla platform transit the entire length of the US-controlled Aleutian Island chain to Shemya Island (a transit just exceeding 1250 nm), where it maintained station for over 20 hours before returning back along the island chain – a total mission time of more than four days.

Afterward, Vanilla supported the Crimson Dragon exercise, which saw the UAV operate for more than 4.5 days providing Link-16 and communications relaying for participating crewed and uncrewed platforms. Launching from NAS Point Mugu, Vanilla held station near the Channel Islands National Park and Santa Barbara Islands transiting more than 6000 nm.

“Its long range and endurance are supported by a 50 gal [189 L] fuel tank; once we’re in the air, we burn about 1.2–1.5 lb/hr [0.54–0.68 kg/hr], or about 20% of a gallon per hour with how Vanilla’s remarkably efficient propulsion system sips the fuel,” Snow explains.

“The powertrain utilises a small, single-cylinder diesel engine, with a shaft directly driving the propeller at the back for dash speeds of 70 kts. It’s a commercial model we can’t disclose, but we quite significantly modify it for our purposes.”

68 kg of payload across seven hardpoints

(Image: Platform Aerospace)

Additionally, the aircraft is built almost entirely from carbon fibre across its wings and fuselage, keeping its MTOW to 620 lb (281 kg) and its endurance to roughly four days if completely loaded to maximum payload (68 kg) and fuel capacity. In addition to the extensive efficiency modifications made to its engine, its aerodynamic and architectural optimisations have leveraged glider characteristics to maximise lift generation and energy efficiency in flight.

Fleet command

The capacity of autonomous vessels to serve as long-endurance, high-speed assets, or as motherships to other uncrewed systems, makes them highly versatile in operating across a range of defence-related applications.

Encapsulating a team heavily specialised in the engineering of uncrewed maritime defence solutions, Skana Robotics has produced numerous different vehicles and subsystem products since its founding in early 2024, although its veritable flagship is the Bull Shark ASV, which is a multirole, tactical-grade vessel capable of carrying payloads of 150 kg including two of the company’s Stingray AUVs.

The ASV has been designed with an emphasis on enabling its movement in contested areas, while maximising its speed and manoeuvrability – its top speed being 50 kts – but also balancing for efficiency and stability such that it can also achieve an operating range of 120 nm.

“We’ve engineered the Bull Shark to be 4 m long, and while the original customer request that spurred its creation did allow for a longer craft, we found that this length, combined with its weight, was optimal for ensuring the best possible stability,” says Guy Shahar, product manager at Skana Robotics.

“It runs on a supercharged gasoline engine producing 330 hp, and its autonomy and manoeuvrability come from a smart integrated control system for accurate steering and throttling, with closed-loop control and a smart INS.

“Specifically, those systems are collectively integrated within Vera, our programmable, ROS2-based, hardware-agnostic command core and edge OS we use on every one of our ASVs, which executes and supervises commands at the Bull Shark’s low-level actuators, as taken from our mission manager and adjusted as makes practical sense using data from the Bull Shark’s sensors and other electronics.”

Vera integrates over remote data links with Skana’s SeaSphere software for mission planning, resource allocation and fleet management, with the level of autonomous decision-making allowed for each connected uncrewed system being configured up or down per operator or CONOPS requirements.

The ASV’s length can also be scaled up or down, to suit requests seeking increased capability or a lower signature, with Skana leveraging a wide supply network of COTS subsystems to fit requested specifications or capabilities. As standard, the vessel integrates a situational awareness camera and a PTZ camera, with considerable space left free for other cameras, as well as sonars, radars and other equipment.

(Image: Skana Robotics)

The company is also developing a new, larger version called the Tiger Shark, which is anticipated as a 7 m length vessel, running on two of the standard Bull Shark’s gasoline powertrains. Once the first prototype’s hull is built, Skana expects to take 3 months to go from subsystem integration to sea trials, viewing this speed of technical development and deployment as indispensable to the requirements of the global defence ASV market, as well as for dual-use customers handling tasks such as coastal security, border monitoring, or search and rescue.

Summary

Over the last few years, we have encountered more than a few individuals claiming themselves the guarantor of warring nations’ victory and peaceful nations’ safety, for having designed a drone or robot that could be mass-produced in the tens of thousands.

But one must not make the mistake of thinking mass alone is enough to win battles or form an impenetrable drone wall along borderlines. Above, we have seen multiple different sizes and configurations of uncrewed systems to match differing military needs, and myriad approaches to development and production besides mass output.

Moreover, relying on one single model of drone, produced in the tens of thousands, means replicating tens of thousands of the same weak point (or points), and is much the reason no army, navy or air force has ever relied on one single vehicle or troop type, or why no uncrewed system uses just one type of sensor.

The future of defence is the future of uncrewed systems, and with symmetric and asymmetric warfare regrettably spreading in many forms around the world, one can expect to see many more types of uncrewed systems being unveiled – including specialised vehicles, multirole and multi-domain systems, tiny and huge alike – in the years to come.

UPCOMING EVENTS