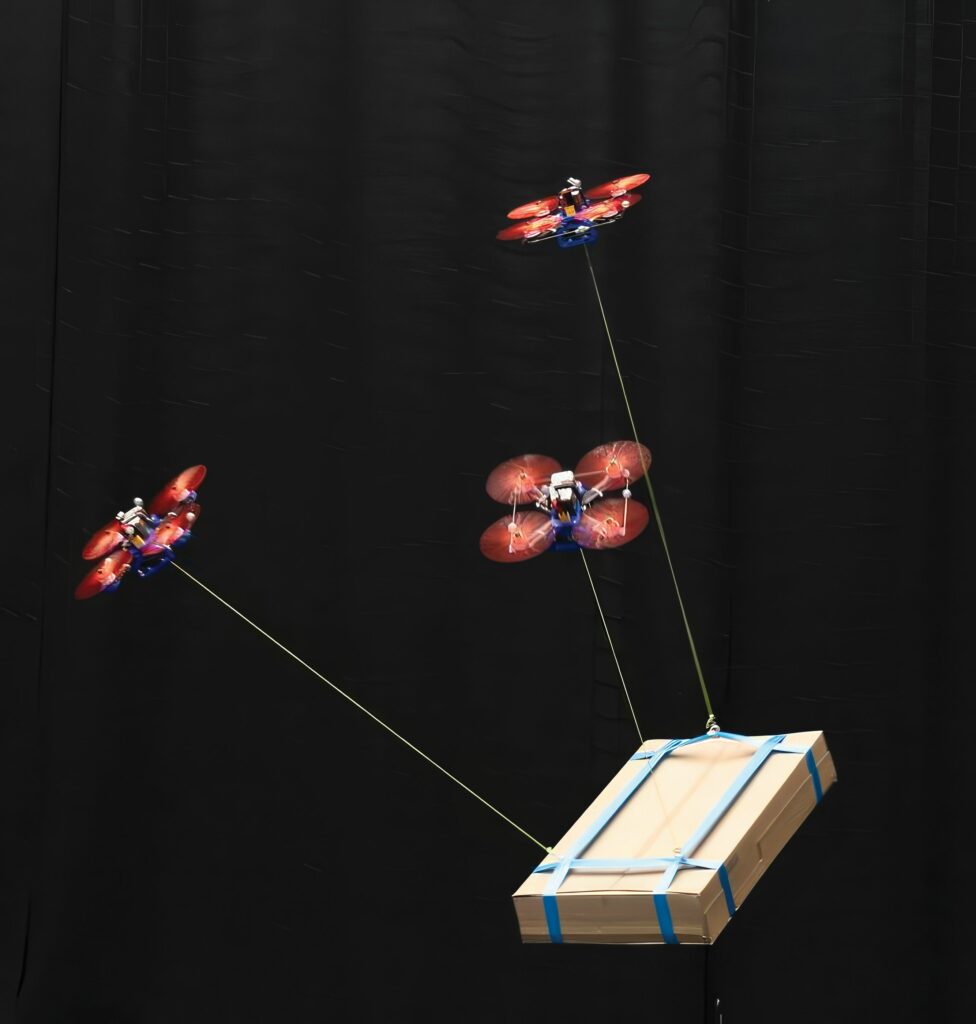

Cooperative lifting

(Image: TU Delft)

A new algorithm allows multiple quadcopters to work together to control and transport heavy payloads, even in windy conditions, writes Nick Flaherty.

The algorithm is suitable for reaching and maintaining hard-to-reach infrastructure, such as offshore wind turbines where harsh weather, limited payload capacity and unpredictable contact with the environment make it difficult to use UAVs.

Existing control algorithms for multi-lifting systems operate only at low speeds and low acceleration because of the complex dynamic coupling between quadrotors and the load.

So, a team at TU Delft in the Netherlands developed an algorithm that controls multiple UAVs in lifting a payload connected with cables. Unlike traditional cascaded algorithms, the trajectory-based framework solves the whole-body kinodynamic motion planning problem online, accounting for the dynamic coupling effects and constraints between the quadrotors and the load.

The planned trajectory is provided to the quadrotors as a reference in a receding-horizon fashion, and is tracked by an onboard controller that observes and compensates for the cable tension. Real-world experiments demonstrated that the framework can achieve at least eight times greater acceleration than state-of-the-art methods.

The teamed quadcopters can even perform complex manoeuvres such as flying through narrow passages at high speed. The algorithm also has high robustness against load uncertainties and wind disturbances and does not require any sensors to be added to the load, demonstrating strong practicality.

“A single UAV can only carry a very limited load,” said Sihao Sun, a robotics researcher at TU Delft. “This makes it hard to use UAVs for tasks like delivering heavy building materials to remote areas, transporting large amounts of crops in mountainous regions or assisting in rescue missions.

“The real challenge is the coordination,” continued Sun. “When drones are physically connected, they have to respond to each other and to external disturbances like sudden movements of the payload in rapid motions. Traditional control algorithms are simply too slow and rigid for that.”

The algorithm adapts to changing payloads and compensates for external forces without requiring sensors on the payload itself, which is an important advantage in real-world scenarios.

“We built our own quadrotor UAVs and tested them in a controlled lab environment,” said Sun. “We used up to four UAVs at once, added obstacles, simulated wind with a fan, and even used a moving payload like a basketball to test dynamic responses.”

Because the UAVs are autonomous, they need to be given only a destination and can navigate independently, adjusting for obstacles and disturbances along the way. “You just tell them where to go, and they figure out the rest,” said Sun.

The system currently uses external motion capture cameras for indoor testing, and is therefore not useful in outdoor environments yet. The team aims to adapt the algorithm for onboard cameras to allow real-world deployment in the future, with potential applications in search and rescue, agriculture and remote construction.

UPCOMING EVENTS